“The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.”

― Albert Camus

To interact is sometimes to resist. To live is sometimes an act of rebellion. To endure, sometimes the very purpose of life. The role of art in resistance – pushing back on whatever that seeks to oppress, violently contain, control or censor – is well studied. What follows is a personal take on my engagement with art, and how it can serve to both document and rally against violence.

The Lionel Wendt Art Gallery, the National Art Gallery, Sapumal Foundation, Paradise Road Galleries, Barefoot Gallery, JDA Perera Gallery, Red Dot and other spaces associated with the visual and performance arts today didn’t exist or were entirely alien to me growing up, in the 80s and early 90s. Colombo at the time was a city of checkpoints, high-walls, barbed wire and armed, stentorian sentries. My parents, who meticulously planned our outings during the day especially during the UNP-JVP ‘bheeshana yugaya’ and when violence in the North strongly suggested retaliatory attacks in the city by way of suicide bombings, never prioritised the arts or visiting the few places at the time one could engage with cultural traditions and practice. In all the family trips to Colombo around thirty years ago, I remember the enduring architectural scars of July 1983 – the soot licked hulls of buildings, flickers of the colours that once adorned houses, the window frames precariously dangling from their hinges, the naked, charred rafters of roofs, the eerie emptiness of certain areas we drove quickly past, the sandbags, camouflage barrels, tin roofed bunkers and barricades. The anxiety was palpable, and the fear, real. I do not know what it was like for the higher echelons of society, but for us, the performance of mundane, daily rituals – going to school or work, going to the neighborhood Sathosa, posting a letter at the sub-post office and getting pasteurized milk from the government co-operative adjacent to it – was the lens through which society beyond was engaged with. It was a very limited frame, in every way imaginable.

Art simply didn’t enter. There was no time to appreciate it. There was no interest in pursuing it.

It was this existence on edge that Thenuwara critiqued, with his take on war and violence through Barrelism. Thenuwara’s art that has since Barrelism undergone many phases and evolved to embrace more contemporary themes, including an enduring violence post-war, remains the cynosure when talking about art, resistance and activism. In a televised interview with the author in 2012, Thenuwara the artist notes how a society and space were, at the time we spoke and since 1983, demarcated and defined with the use of barbed wire, hiding in plain sight the violence embedded the architecture. Thenuwara the activist went on to note how his artistic gaze and critical output informed his advocacy around educational reform, as the basis for a renewed social contract that could serve to both memorialise the past better, and thus avoid forever returning to it.

There is much more that defines an artistic landscape, particularly after 2009, by range and depth – a study of which I am ill-placed to record save for a few, deeply personal frames of reference, shared here. My interest in and engagement with the visual arts began during my undergraduate years at Delhi University, at the same time now critically acclaimed and world-renowned artist T. Shanaathanan was doing his MFA. My first acrylic encounter and artistic framing of Sri Lanka and its violence was through his art, in, of all place, New Delhi. Since then I have been interested in the intersection of rights, witnessing, technology and activism. Shanaathanan continues to define, for me, an artistic endeavour to bear witness to inconvenient truths that is intellectually engaging, never sterile, continuously refined and inclusive. An art that informs illuminates and ultimately, is a call for engagement. Content that subverts, presenting the ordinary as a gateway or frame to inquire and question. As noted by me in Open Magazine after I saw Shanaathanan’s ‘Cabinet of Resistance’ at the Kochi-Muziris Art Biennale in 2017,

“By presenting the lives of others through this work, [he] is able to transport us, through index cards, into the banality of violence, in all its forms— beyond the enfilade of a battlefield, to the domestic; beyond the headline-grabbing deaths, to loss so painful it can only ever be told as parable; away from the communal to the deeply personal.”

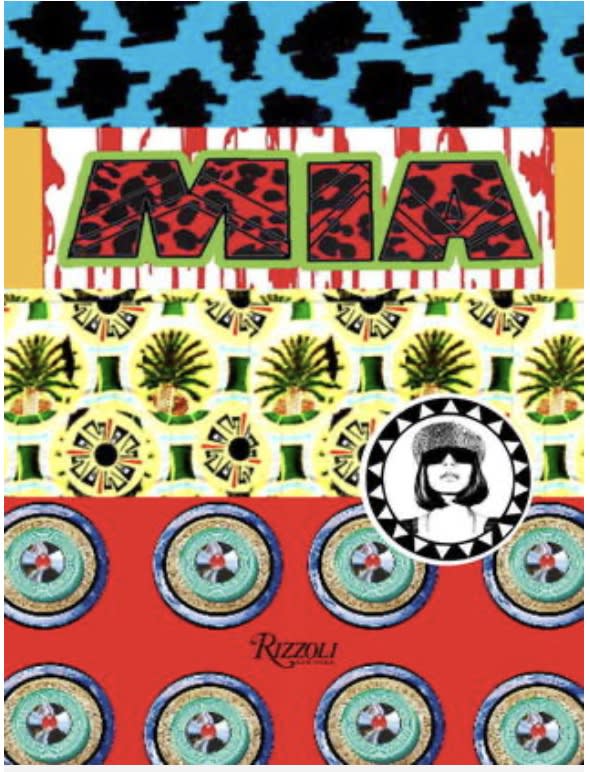

In a very different way, the singer-songwriter M.I.A. (Mathangi ‘Maya’ Arulpragasam) has an interesting art book based on her music, and what inspires it. M.I.A. is more popular outside of Sri Lanka than in the country, where her considerable talent in music isn’t recognized by local radio stations, perhaps because of controversies surrounding her equally considerable ignorance of domestic politics outside of histrionic sound bites. M.I.A.’s self-titled book, available on Amazon, is a compelling, unusual visual story of resistance and violence – embracing everything from digital photo editing to video stills, drawings, media recording other media, deliberate visual and data corruption, lyrics, various prints and other assorted paraphernalia. There is method to this madness, for what the book frames are unique perspectives of the systemic nature of racism in Sri Lanka, which for most, to date, remains largely invisible.

It’s relatively easy to flag and find the more popular and visible acts of resistance and activism through art in Sri Lanka. It’s harder to appreciate the smaller acts of artistic resistance – street and performance art, mural, graffiti, symbols and signs in public spaces. Godwin Constantine’s 1994 performance ‘Broken Palmyrah’, Haththotuwegama’s street theatre and the creative scripts and performances during the ‘Bheeshana Yugaya’. The last is wonderfully documented by Ranjini Obeysekara in her seminal book Sri Lankan Theatre in a Time of Terror: Political Satire in a Permitted Space, which notes that scripts during the height of the JVP violence in the late 80’s foresaw violent police intervention at the end of a play to break up performance and audience, and wrote this into plot and action. There are many markers of a rich tradition of resistance in the performance spaces and theatrical traditions of Sri Lanka. Post-war, through the Colombo Dance Platform, Colomboscope and smaller platforms facilitated by Theertha and other artistic collectives, performance as resistance and reflection has seen an up-surge, dealing with complex yet urgent social, political, economic and cultural issues mainstream artists, with a more commercial bent, have shied away from.

Post-war, as Saskia Fernando flags in a 2015 article published in Kalaa Kathaa, the growing availability and redefinitions of public space has resulted in site-specific art as well as more traditional art, and performance, being respectively showcased or staged in multiple, diverse venues. This has collectively brought art closer to ordinary citizens, and provides entry points for those who have no desire to collect art, or read essays like this, but nevertheless want and like to interact with what art frames, flag or surfaces, free and accessible ways to do so. This is important. It encourages interaction and reflection with audiences that are diverse, and vitally, young. Aside from the appreciation of what’s shown, or performed, art fertilizes a neural resistance to supine conformity, blind trust, rote and regurgitation, the fundamental tenets of authoritarianism.

Art makes you think differently, observe, and not just see, listen, and not just hear.

Today, Facebook memes form and frame individual acts of resistance. From cartoon and satire to animated GIFs and short videos, the rise of social media has spurned new forms, techniques of and platforms for art that offer new engagement dynamics. The subjects of critique find they can no longer capture, contain, censor or kill art, and its producers, easily. Where does an artist like Pradeep Chandrasiri, a victim of a torture camp, and whose art responds to personal trauma, stand in this landscape? On Instagram, thousands follow visual artists like Muvindu Binoy and Firi Rahman who consciously and consistently use a critical lens, through photography or mixed media, to explore the world around them.

How can we appreciate Jagath Weerasinghe post-war, as an artist who inspired so many in the 90s yet unwilling, or perhaps more unkindly, unwilling to engage with newer dynamics of conflict that stem from older systemic violence? Do the old masters have relevance in a digital age? These are questions I tried to address in ‘Mediated’, a show I was invited to create and curate by Saskia Fernando Gallery in 2012 that brought together a social pollster, constitutional theorist, acclaimed author and economist with artists, architects, a DJ, and graphic designer. The show was aimed at a younger audience, to lure them into a space and by a modern aesthetic, combined with a robust gaze that in turn was informed by solid research and writing, help them engage with contemporary realities in ways they would not otherwise have thought of.

And therein lies the rub – how to inspire, into the future, art that is deeply critical and yet appeals to more than those already tuned into the politics of the frame, space or performance. Gallerists and curators will have a key role in this, imagining first new frames that artists are invited to inhabit, collaborate within and ultimately, redefine. But there is roles for us too – as those who see art and by that action, help define it, to help a rich tradition of art-based activism grow. There is of late a tendency to hide the artist’s confusion and intellectual under-development in highfalutin descriptions of their work, which ‘sound’ artistic because they are incomprehensible to most. Curators of leading art platforms have held hostage the potential of artists, space and context to their own inability to frame, focus or fertilize. We need a stronger culture of critical review – where to robustly critique is not seen as an affront to person, production or tradition, but a vigorous and rich debate of ideas.

The domain of artistic production may be alien to many of us, but the necessity of championing activism and advocacy as being rooted to citizenship and its exercise must never escape us.

Ultimately, it is not just about the art and artist. What and how we appreciate is a reflection of ourselves, and what kind of society and world we would like to see. Often, the most powerful and first glimpses of what can be our future, based on readings of past and present, is through the abstract, ephemeral frames art affords. To be meaningfully involved in the arts doesn’t require affluence or influence. It only asks of us to reflect deeply about what we have read, heard, touched or seen, how we feel about it and to then apply a similar degree of critical reflection in all aspects of life. The subversive power of art thus lies not in its output per se, but in how it can contribute to an inquiring society.

And that is why, for me, why though politics may at times be art, art is always political.

– Article by Sanjana Hattotuwa